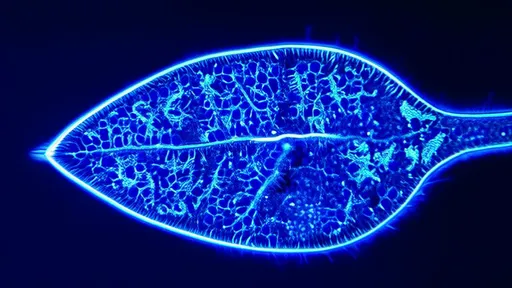

In the quiet, boggy habitats where the Venus flytrap lies in wait, a sophisticated electrical drama unfolds each time an unsuspecting insect brushes against its sensitive trigger hairs. This carnivorous plant, known scientifically as Dionaea muscipula, does not possess a nervous system like animals do, yet it exhibits a form of rapid signaling that bears a striking and fascinating resemblance to neural conduction. The mechanism behind this phenomenon involves the propagation of action potentials across its specialized leaf structures, creating a functional, plant-based analog to an animal’s neural network.

At the heart of the Venus flytrap’s predatory success is its ability to detect prey and respond with astonishing speed. Each of the trap’s inner lobes is equipped with several trigger hairs. When stimulated—typically by the movement of an insect—these hairs act as mechanical sensors, initiating an electrical signal known as an action potential. This is not a mere simple reflex; it is a complex, threshold-based process. The plant must register multiple touches within a short period to avoid closing for false alarms like falling debris, indicating a form of primitive memory and decision-making.

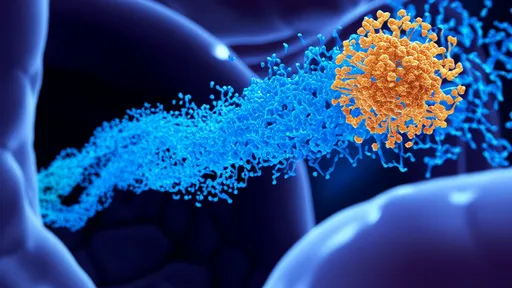

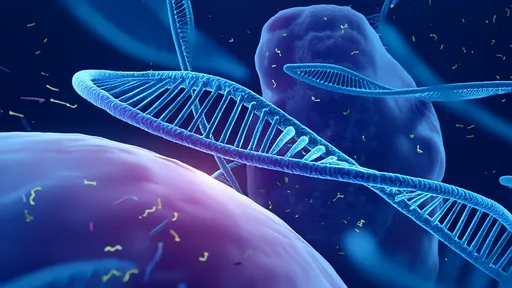

The action potential itself is an electrochemical wave that travels through the plant’s tissues. Ion channels in the cell membranes open and close, allowing a rapid flux of ions, particularly calcium and potassium, which depolarize the membrane in a manner eerily similar to what occurs in animal neurons. This depolarization propagates from cell to cell, moving through the parenchyma and vascular tissues at a speed of about 20 millimeters per second. While slower than most animal nerve impulses, this is remarkably fast for a plant, allowing the trap to close within seconds of the final triggering stimulus.

What is especially intriguing is the network-like nature of this signaling. The action potentials do not merely travel along a single path; they can spread through a tissue network, coordinating the trap’s movement. Research has shown that the trap’s lobes are electrically integrated, allowing the signal to propagate across the entire structure. This ensures a synchronized closure, curving the lobes together to form a cage around the prey. The electrical signal is then followed by biochemical changes, including the acidification of the trap’s interior and the secretion of digestive enzymes.

This mechanism raises profound questions about the evolutionary origins of electrical signaling in life. The ion channels and pumps involved in the flytrap’s action potentials are homologous to those found in animal nerves, suggesting a deep evolutionary kinship. Plants and animals last shared a common ancestor over a billion years ago, and the building blocks for electrical excitability appear to have been present even then. In the Venus flytrap, these ancient tools have been co-opted for a unique and dramatic purpose: carnivory.

Scientists are keenly studying this system not only to understand plant biology but also to draw inspiration for new technologies. The field of plant neurobiology, though controversial in its name, explores how plants process information from their environment without a central nervous system. The flytrap’s ability to count stimuli, make decisions, and remember prior events—all mediated by electrical networks—offers a model for biomimetic computing and soft robotics. Imagine adaptive materials or sensors that operate on similar principles, using ion fluxes instead of electrons to process information.

Moreover, the study of electrical signaling in plants like the Venus flytrap challenges our anthropocentric views of intelligence and responsiveness. It demonstrates that complex behaviors do not require a brain or neurons but can emerge from distributed networks of excitable cells. This expands the concept of cognition and adaptability in the biological world, suggesting that plants are far more dynamic and interactive than traditionally believed.

In summary, the Venus flytrap’s action potential-based signaling system is a marvel of natural engineering. It functions as a neuro-like network, enabling rapid, coordinated movement in response to environmental cues. This system underscores the evolutionary ingenuity of plants and provides a captivating glimpse into the shared electrophysiological language of living organisms. As research continues to unravel the details of this mechanism, it not only deepens our appreciation for botanical complexity but also opens new avenues for interdisciplinary innovation.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025