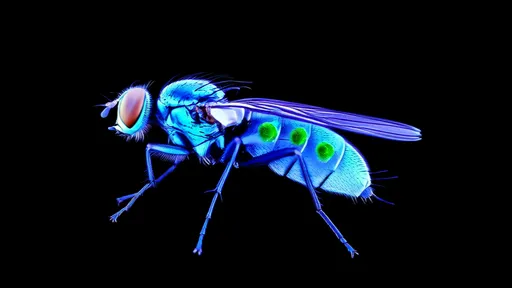

In the ever-evolving field of ecological research, a groundbreaking technique has emerged that is reshaping how scientists monitor insect biodiversity. By analyzing environmental DNA (eDNA) collected from air samples, researchers can now detect and identify insect species without ever laying eyes on them. This non-invasive method is not only revolutionizing data collection but also offering unprecedented insights into the health and composition of ecosystems worldwide.

The concept of eDNA itself is not entirely new; it has been used for years in aquatic environments to track species like fish or amphibians through water samples. However, applying this technology to air samples for insect monitoring is a relatively recent innovation. The process involves capturing airborne DNA—often shed from insects in the form of scales, hairs, secretions, or even entire microscopic particles—and sequencing it to reveal the genetic signatures of present species. What makes this approach so powerful is its ability to survey vast areas quickly and efficiently, providing a snapshot of biodiversity that would be incredibly time-consuming to achieve through traditional methods like visual counts or trapping.

One of the most significant advantages of air-based eDNA monitoring is its sensitivity. Even in cases where insect populations are sparse or elusive, trace amounts of DNA can be detected, allowing for the identification of rare or endangered species that might otherwise go unnoticed. This is particularly crucial in the context of global insect declines, which have raised alarms among conservationists and policymakers alike. With air sampling, scientists can gather data on population trends, distribution changes, and the impacts of environmental stressors such as climate change or habitat loss with a level of detail that was previously unattainable.

Moreover, this technology minimizes human disturbance to ecosystems. Traditional survey methods often require physical intrusion—setting up traps, handling specimens, or traversing sensitive habitats—which can inadvertently harm the very environments under study. Air sampling, by contrast, can be conducted from a distance using passive collectors or drones, reducing the ecological footprint of research activities. This aspect is especially valuable in protected or remote areas where preserving natural conditions is paramount.

The applications of air eDNA for insect monitoring are vast and varied. In agriculture, it can help track pest species and inform integrated pest management strategies, reducing the need for broad-spectrum pesticides. In public health, it offers a tool for surveilling disease vectors like mosquitoes, enabling early warnings of outbreaks. For conservation, it provides a means to assess the effectiveness of restoration projects or protected areas by monitoring changes in insect communities over time. Even in urban settings, air eDNA can reveal how green spaces influence biodiversity, offering insights for sustainable city planning.

Despite its promise, the technique is not without challenges. Contamination is a persistent concern; airborne DNA can come from a multitude of sources, and ensuring that samples are not polluted by external genetic material requires rigorous protocols. Additionally, the interpretation of eDNA data demands sophisticated bioinformatics tools to distinguish between species, especially those with similar genetic profiles. There is also the matter of "dark DNA"—genetic material from unknown or poorly documented species that complicates identification efforts. Researchers are actively working to refine methods and build comprehensive reference databases to address these issues.

Looking ahead, the integration of air eDNA monitoring with other technologies holds exciting potential. Coupling it with remote sensing or machine learning algorithms could automate data analysis and enhance predictive modeling. As sequencing costs continue to drop and analytical capabilities improve, this approach is likely to become a standard tool in ecological and environmental management. It represents a leap forward in our ability to understand and protect the intricate web of life that insects represent—a group that underpins critical ecosystem services from pollination to nutrient cycling.

In conclusion, the use of environmental DNA from air samples to monitor insect diversity is more than just a technical advancement; it is a paradigm shift in how we observe and interact with the natural world. By harnessing the genetic clues left behind in the air, scientists are opening a new window into biodiversity, one that promises to inform conservation efforts, support sustainable practices, and deepen our appreciation for the small yet mighty creatures that shape our planet.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025