For decades, the central dogma of evolutionary biology has rested firmly on the shoulders of genetic mutation and natural selection. The narrative was straightforward: random changes in DNA sequence create variation, and environmental pressures select the fittest variants, gradually shaping species over generations. While this framework remains foundational, a growing body of research is compelling scientists to expand their view. The emerging field of evolutionary genetics is now grappling with a powerful and once-heretical idea: that non-genetic, epigenetic mechanisms can also influence the pace and direction of adaptive evolution.

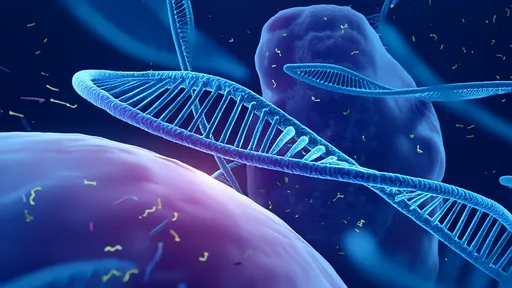

Epigenetics refers to the molecular modifications that regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Think of it as a sophisticated layer of software instructions operating on the hardware of the genome. These instructions include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA molecules. They can turn genes on or off in response to environmental cues, allowing an organism to fine-tune its physiology rapidly. The revolutionary and contentious proposition is that these environmentally induced epigenetic changes can sometimes be inherited across generations, potentially providing a substrate for natural selection to act upon, thereby facilitating adaptation faster than waiting for random genetic mutations.

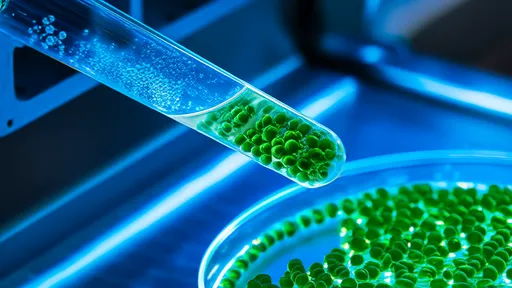

The evidence for this phenomenon is accumulating from diverse corners of the natural world. In plants, which seem to be masters of epigenetic regulation, studies have shown that exposure to stressors like drought or herbivores can trigger epigenetic changes that are passed to offspring, equipping them with better resistance. This transgenerational inheritance offers a plausible explanation for how sessile organisms, unable to flee from adversity, can adapt so swiftly to changing conditions. It suggests a form of Lamarckian inheritance—the inheritance of acquired characteristics—operating alongside classic Darwinian mechanics.

Animal models provide equally compelling cases. Researchers have observed that dietary changes, toxin exposure, or even psychological stress in parents can lead to epigenetic alterations in their offspring, affecting traits like metabolism, stress response, and behavior. These are not mere physiological carryovers; they represent molecular marks on the genome that can persist for more than one generation. This blurs the traditional distinction between an organism's rigid genetic inheritance and the flexible, lifetime experiences it accumulates.

Perhaps the most profound implication of this research is the challenge it poses to the Modern Synthesis. The long-held view that evolution is a slow, blind process of filtering random genetic errors is being complemented by a recognition of a more responsive and dynamic system. Epigenetics introduces a mechanism for directed variation. The environment doesn't just select from random variation; it can, in a sense, help create specific, heritable variation upon which it can then select. This suggests evolutionary pathways can be more predictable and rapid than previously thought, especially in the short term.

However, the field is not without its fervent debates and skeptics. A major point of contention is the stability and longevity of epigenetic marks across evolutionary timescales. While they can clearly last for several generations, can they persist for hundreds or thousands of generations, truly shaping the fate of a species like a DNA mutation can? Critics argue that many observed cases of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance might be short-lived physiological effects or statistical artifacts, rather than a consistent and powerful evolutionary force. Distinguishing between the effects of true epigenetic inheritance and shared environmental factors or cultural transmission in animals remains a significant methodological hurdle.

Furthermore, the interplay between genetic and epigenetic evolution is incredibly complex. Epigenetic changes can influence the rate of genetic mutation in specific genomic regions. Conversely, genetic mutations can create or destroy the regulatory sites necessary for epigenetic marking. They are not separate systems but are deeply entangled in a co-evolutionary dance. Evolution likely acts on both the genome and the epigenome simultaneously, with each influencing the other's potential for change.

This new perspective forces a reconsideration of how we conserve biodiversity in a rapidly changing world. If populations can adapt through both genetic and epigenetic means, understanding a species' epigenetic potential—its capacity for flexible, rapid response—becomes as crucial as understanding its genetic diversity. Species with high epigenetic plasticity might be more resilient to climate change, habitat loss, and pollution, offering a new metric for predicting which populations are most vulnerable or most likely to survive the Anthropocene.

In conclusion, the evidence for the role of epigenetic regulation in adaptive evolution is no longer a fringe idea but a serious and vibrant area of scientific inquiry. It does not seek to overthrow the bedrock principles of evolutionary theory but rather to enrich them. It paints a picture of evolution that is more nuanced, more rapid, and more interactive than the classic gene-centric view. The genome is not a static, immutable blueprint but a dynamic, responsive system. The environment writes upon this system through epigenetic marks, and sometimes, that writing is passed down, offering future generations a head start in the relentless race for survival. The story of evolution, it turns out, has more authors than we once believed.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025