The intersection of wastewater treatment and renewable energy generation has long been a subject of scientific inquiry, but recent breakthroughs in microbial fuel cell (MFC) technology are turning this theoretical possibility into a tangible reality. Microbial batteries, as they are colloquially known, harness the metabolic activity of bacteria to break down organic matter in sewage while simultaneously producing electricity. This dual-purpose innovation could revolutionize both the energy and water sectors by transforming waste treatment plants from energy consumers into power producers.

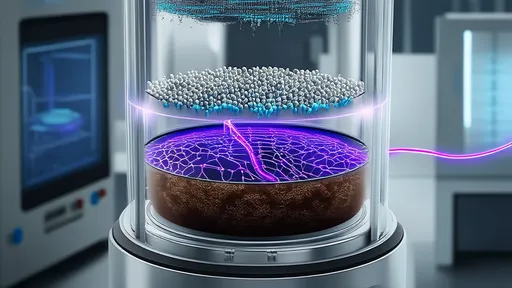

At the heart of this technology lies a simple yet profound biological principle: certain electroactive microorganisms naturally release electrons as they digest organic compounds. When properly channeled through an electrochemical system, these electrons create a current that can be harvested. Unlike conventional wastewater treatment that requires significant energy input for aeration and processing, microbial batteries flip the script by extracting value from what was previously considered mere waste.

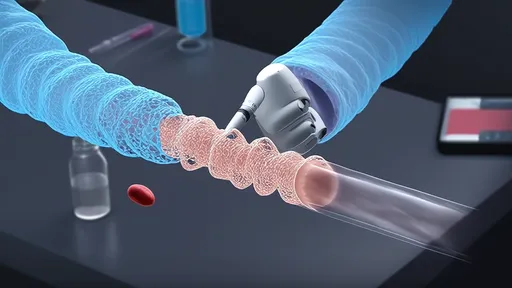

The engineering behind microbial batteries resembles traditional fuel cells but with critical biological components. A typical setup consists of an anode chamber where wastewater flows past biofilm-coated electrodes, a cathode chamber that facilitates oxygen reduction, and a proton-exchange membrane separating the two. As bacteria on the anode oxidize organic pollutants, they transfer electrons to the electrode while protons migrate through the membrane. The resulting electron flow generates usable electricity even as the water becomes progressively cleaner.

Recent pilot projects demonstrate the technology's practical potential. A municipal treatment facility in Oregon has successfully integrated MFCs into its secondary treatment process, achieving 85% organic removal while powering its monitoring systems. Similarly, a brewery in Germany uses microbial batteries to pretreat high-strength wastewater, offsetting 15% of its energy consumption. These real-world applications prove that the technology can scale beyond laboratory settings.

What makes microbial batteries particularly compelling is their ability to handle diverse waste streams. From domestic sewage to agricultural runoff and industrial effluents, different microbial communities adapt to specific pollutant profiles. Researchers have identified particular strains like Geobacter sulfurreducens and Shewanella oneidensis that excel at electron transfer, while mixed cultures often outperform pure strains in real-world conditions where wastewater composition fluctuates.

The environmental implications extend beyond energy production. Conventional treatment plants emit greenhouse gases like methane and nitrous oxide during organic matter decomposition. Microbial batteries minimize these emissions by diverting electron flow toward electrodes rather than anaerobic respiration pathways. Early lifecycle assessments suggest that widespread MFC adoption could reduce the wastewater sector's carbon footprint by 30-50% while creating a decentralized energy infrastructure.

Economic barriers remain the primary hurdle for large-scale implementation. While the concept works brilliantly in controlled environments, scaling up requires overcoming material costs and power density limitations. Current systems produce roughly 1-2 watts per square meter of electrode surface—enough for sensors but insufficient for grid-scale generation. Innovations in electrode materials, membrane design, and system architecture aim to boost output while lowering capital expenses.

The future may lie in hybrid systems that combine microbial batteries with complementary technologies. Some research teams integrate MFCs with constructed wetlands for small communities, while others pair them with anaerobic digesters to maximize energy recovery. There's growing interest in stacking multiple MFC units or combining them with photovoltaic systems, creating wastewater treatment plants that operate entirely off-grid. As material science advances and production scales, microbial batteries could become standard features in next-generation infrastructure projects.

Beyond municipal applications, microbial batteries show promise for addressing environmental justice issues. Remote communities and developing regions often lack both sanitation infrastructure and reliable electricity. Compact MFC systems could provide decentralized solutions where traditional treatment plants prove impractical. Field tests in rural India and sub-Saharan Africa demonstrate how simple, low-maintenance units can improve public health while powering essential services like lighting and water pumps.

The scientific community continues pushing boundaries with creative configurations. Recent experiments explore floating MFCs for lake remediation, sediment-based systems for ocean monitoring, and even miniature versions for educational purposes. As genetic engineering advances, researchers may develop tailored microbial communities optimized for specific waste streams and energy outputs. The convergence of biotechnology, materials science, and environmental engineering promises to unlock microbial batteries' full potential.

While technical challenges persist, the fundamental premise remains compelling: every community produces wastewater, and microbial batteries offer a pathway to transform this liability into an asset. As climate change intensifies the search for sustainable solutions, this technology represents a rare win-win scenario—cleaner water and cleaner energy from a single process. The coming decade will likely determine whether microbial batteries remain a niche innovation or emerge as a cornerstone of circular economy infrastructure.

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025