In the vast expanse of the cosmos, measuring the rate of the universe's expansion has long been one of astronomy's greatest challenges. For decades, scientists have relied on traditional "standard candles" like Cepheid variables and Type Ia supernovae to gauge cosmic distances. But now, a groundbreaking method using gravitational waves is emerging as a transformative tool—one that could redefine our understanding of the Hubble constant and resolve one of modern cosmology's most persistent controversies.

The concept of gravitational waves as standard candles hinges on their unique properties. Unlike light, these ripples in spacetime—first predicted by Einstein and directly detected in 2015—travel unimpeded through the universe. When two massive objects like neutron stars collide, they produce both gravitational waves and electromagnetic radiation. By comparing the gravitational wave signal's amplitude (which reveals the intrinsic distance) with the observed brightness of accompanying light emissions, astronomers can calculate the expansion rate of the universe with unprecedented precision.

What makes this approach revolutionary is its independence from the traditional "cosmic distance ladder." Conventional methods require painstaking calibration across multiple rungs—parallax measurements for nearby stars, Cepheids for intermediate distances, and supernovae for far galaxies—with errors compounding at each step. Gravitational waves, however, provide a direct measurement of distance without relying on this fragile chain. The merger of neutron stars effectively becomes a "standard siren" (the gravitational wave analog to a standard candle), emitting both spacetime ripples and light in a coordinated cosmic announcement.

Recent observations have demonstrated the power of this technique. The landmark GW170817 event—the first neutron star merger detected via both gravitational waves and gamma rays—allowed scientists to derive a Hubble constant value that intriguingly straddled the two conflicting estimates from supernovae and cosmic microwave background measurements. While this single data point couldn't resolve the tension, it validated gravitational waves as a viable third pathway for measuring cosmic expansion.

The implications extend far beyond academic curiosity. The current discrepancy in Hubble constant values—roughly 67 km/s/Mpc from the early universe's CMB versus 73 km/s/Mpc from late-universe supernovae—suggests either systematic errors in our measurements or, more excitingly, new physics beyond our current cosmological models. Gravitational waves offer a fresh perspective that could break this deadlock. Their distance measurements rely on different physics than light-based methods, providing an independent check that could reveal which existing approach (if either) holds the truth.

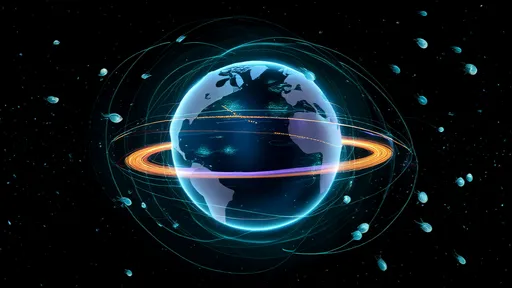

As gravitational wave detectors like LIGO, Virgo, and the upcoming LISA array improve in sensitivity, the data floodgates are beginning to open. Projections suggest that within a decade, astronomers may detect hundreds of neutron star mergers annually. Each collision serves as a potential standard siren, allowing statistical determination of the Hubble constant with shrinking error bars. Future observations might even detect mergers at much greater distances than current electromagnetic standard candles can reach, probing the expansion rate across different cosmic epochs.

Challenges remain, of course. The gravitational wave method currently requires the rare coincidence of detecting both spacetime ripples and electromagnetic counterparts—a difficult task given that most mergers happen too far away for our telescopes to spot the light. Moreover, the precision depends on accurately modeling the neutron stars' complex dynamics during collision. But as multi-messenger astronomy matures and next-generation instruments come online, these obstacles appear increasingly surmountable.

Beyond measuring the Hubble constant, gravitational wave standard sirens promise to illuminate other cosmic mysteries. They could help constrain the nature of dark energy, test general relativity in extreme environments, and provide new insights into neutron star physics. Some theorists even speculate they might reveal signs of extra dimensions or other exotic phenomena that could reshape our fundamental understanding of reality.

For now, the astronomy community watches with bated breath as this new cosmic yardstick proves its worth. In the coming years, gravitational waves may not just serve as messengers of cataclysmic events, but as the definitive arbiters in one of cosmology's greatest debates—finally answering how fast our universe is growing, and perhaps revealing why previous methods couldn't agree. The era of gravitational wave cosmology has arrived, and with it, a powerful new lens through which to view the expanding tapestry of our cosmos.

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025