In the dimly lit corridors of abandoned research facilities and forgotten server farms, a quiet revolution is brewing. Across the globe, artificial intelligence systems are sifting through mountains of discarded experimental data—failed trials, discontinued projects, and half-finished research—extracting value from what was once considered scientific debris. This emerging practice, colloquially termed "dark data alchemy," represents a paradigm shift in how we perceive failure in the age of machine learning.

The concept hinges on a simple but profound realization: in science, negative results and abandoned experiments contain latent patterns that often elude human researchers. Where human eyes see only dead ends, neural networks detect subtle correlations and hidden pathways. A 2023 study by the Turing Institute revealed that approximately 83% of all scientific data generated never sees publication—a vast reservoir of untapped potential now being mined by sophisticated AI tools.

At the forefront of this movement is Dr. Elara Voss, whose team at the Copenhagen Institute of Technological Archaeology has developed Phoenix, an AI system specifically designed to "resurrect" discontinued pharmaceutical research. "We've identified seventeen previously abandoned drug candidates that show real promise against antibiotic-resistant bacteria," Voss explains. "These were all trials that showed insufficient efficacy in narrow contexts but contain molecular combinations that our models recognize as potentially effective against modern superbugs."

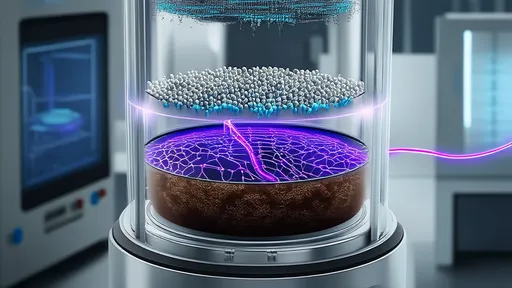

The process begins with what researchers call "data archaeology"—the careful extraction and reconstruction of incomplete or poorly documented experimental records. Unlike traditional data mining, this often involves piecing together fragmented information from lab notebooks, outdated digital formats, and even handwritten marginalia. Advanced natural language processing models then contextualize these fragments within contemporary scientific frameworks.

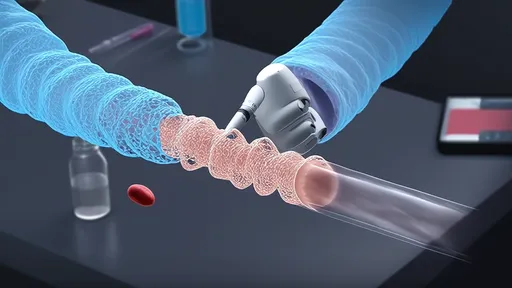

One striking success story comes from Japan, where a team at Kyoto University applied dark data alchemy to decades of abandoned robotics research. Their AI system Yomigaeri (Japanese for "revival") identified a peculiar hydraulic actuator design that had been discarded in 1997 due to material limitations. "The original researchers couldn't manufacture the required flexible ceramics," explains project lead Kenji Tanaka. "But with modern 3D printing techniques, we've built prototypes that outperform current models by 40% in energy efficiency."

Critics argue that the approach risks creating a sort of scientific necromancy—breathing false life into ideas that were abandoned for good reason. Dr. Miriam Kostova of Harvard's Ethics in AI Lab cautions: "There's a danger of confirmation bias in how we train these systems. If we only look for 'hidden gems' in failure, we might overlook the fundamental reasons those projects failed." Her team has developed protocols to ensure that resurrected research undergoes rigorous validation before application.

The business implications are equally profound. Venture capital firms have begun establishing "dark data funds" specifically to commercialize rediscovered research. Silicon Valley's Aurelian Ventures recently raised $300 million for this purpose, with partner Raj Patel noting: "It's not just about individual discoveries. We're seeing entire new fields emerge from connecting dots between unrelated abandoned projects. The patent landscape is being quietly rewritten."

Perhaps most intriguing are the philosophical ramifications. Dark data alchemy challenges our fundamental notions of scientific progress. As Oxford philosopher of science Thomas Yorke observes: "We've long operated under the assumption that the scientific method naturally filters out inferior ideas. But what if, like actual alchemists, earlier researchers were simply missing the right tools to see the gold hidden in their failed experiments?" This perspective is sparking heated debates in academic circles about the nature of discovery and the value of preserving all research data indefinitely.

Practical applications continue to emerge at a remarkable pace. In materials science, AI systems have identified previously overlooked alloy combinations with superconducting properties. Climate researchers have found valuable atmospheric data in abandoned weather balloon experiments from the 1950s. Even NASA has begun applying these techniques to sift through decades of spacecraft telemetry that was initially deemed unusable due to sensor malfunctions.

The movement has also spawned new academic specialties. Universities from Munich to Mumbai now offer courses in "experimental archaeology" and "data paleontology." The Massachusetts Institute of Technology recently established the world's first Dark Data Studies department, complete with a specialized library containing physical backups of research that might otherwise become unreadable as digital formats evolve.

As the field matures, ethical guidelines are struggling to keep pace. Complex questions arise about intellectual property rights when AI systems derive new insights from decades-old, orphaned research. The legal status of discoveries made from corporate research that was intentionally abandoned remains particularly contentious. International scientific bodies are now racing to establish frameworks for what some are calling "posthumous collaboration" between contemporary researchers and their predecessors.

Looking ahead, proponents believe dark data alchemy could fundamentally alter the economics of research and development. "We're entering an era where no experiment is truly wasted," suggests tech entrepreneur Lina Kovac, whose startup Alchemetrics has developed AI tools for industrial R&D departments. "The potential efficiency gains are staggering—imagine reducing duplicate research efforts by even 20%. We're talking about trillions in global savings."

Yet for all its promise, the practice remains intensely labor-intensive. Cleaning and contextualizing decades-old data often requires painstaking manual work before AI systems can begin their analysis. This has led to calls for standardized "research wills"—formal documentation procedures to ensure future accessibility of contemporary experiments, regardless of their immediate outcomes.

As the sun sets on another day at a converted warehouse in Berlin—home to one of Europe's largest dark data processing centers—rows of servers hum with activity, their algorithms sifting through the digital ghosts of abandoned dreams. Here, in the interplay between silicon and forgotten human endeavor, a new chapter of discovery is being written. Not through bold leaps into the unknown, but by carefully listening to the whispers of what was once dismissed as failure.

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025